Revisionism in the Wake of Covid

A dialogue confronting the premise of revisionist efforts to diminish the pandemic's severity and dismantle public health institutions.

A Preamble

Greg Gibson is a friend and colleague based at Georgia Tech where he is a Regents Professor of Biology and Director of the Center for Integrative Genomics. Greg and I collaborated together as part of GT’s institutional response to Covid — helping to design, build, and implement an asymptomatic testing campaign in advance of the return to classes in Fall 2020. Five years later much has changed. There are new epidemic threats and a concerted effort to undermine public health experts and expertise, abetted by revisionist takes on Covid’s severity. Greg approached me earlier in the summer after the release of “In Covid’s Wake” with the idea of discussing a broader set of issues. It took us some time but the issues have only grown in relevance. You can find our dialogue below & more of Greg’s writing at this link.

A Dialogue on Covid Revisionism

Greg: In The Plague, Albert Camus has his protagonist, Dr. Rieux, contemplating an outbreak in his town, comment “I have no idea what's awaiting me, or what will happen when this all ends. For the moment I know this: there are sick people and they need curing.” That was certainly the sentiment in medical circles in early 2020 as SARS-CoV-2 was emerging, so I was a little surprised to see the new book In Covid’s Wake: How our Politics Failed Us by self-described progressive Princeton political scientists Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee, making the case that the inability of liberal academia to tell the truth led to a failed pandemic response. Then this month The Atlantic has an article asking whether “Covid revisionism has gone too far”, so I thought we could have a conversation about it. The Macedo and Lee argument seems to be that in retrospect the pandemic was not that bad, that all of the economic disruption and home schooling and social distancing was too high a price to pay for saving a million lives. They argue that it was known that non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) don’t work and imply that if only we had let the virus spread through young people quickly there would have been less reliance on vaccines that did not halt the virus in its tracks anyway. In a sense then, all the anti-science politics and divisiveness we see in America now is public health’s fault. Is that a fair summary?

Joshua: That is a fair summary of their argument – even if Macedo and Lee misrepresent what actually happened during the pandemic. Covid was in fact devastating and NPIs did make a difference as a gateway to life-saving vaccines that turned the tide. In total, more than 1.2 million Americans died of COVID, including hundreds of thousands who chose not to get vaccinated, and likely a million or more lives were saved because of reduced infection rates in 2020 and the subsequently availability of vaccines in 2021. So, at its core, the premise that the pandemic was not that bad is one that we will have to unpack here, at least in part. Macedo and Lee try to avoid confronting this reality because it is, one might say, inconvenient. They are experts in politics and public affairs. Distance can sometimes bring objectivity and real questions have been asked for multiple years on increasing the efficacy and reducing the costs of public health interventions. So, I read the book with hope that I would learn something.

Greg: A lot of the revisionism here seems to me to ignore how dire things looked in March of 2020 when Covid-19 was devastating northern Italy and hospitals were becoming completely overwhelmed in New York city. The case fatality rate looked like it would be at least 1%, maybe double that and an order of magnitude higher for the elderly and infirm. The transmission ratio – the number of new infections resulting from each infected person – was at least 3, and without intervention to slow that down, we were looking at between 1 and 2 million American deaths. An obscure report (prominently cited in their book) from Johns Hopkins denying that NPI are efficacious was never going to sway the CDC, and nor should it have. While there was a lot of misinformation, particularly around masks and whether transmission was by aerosol, it was a period of great uncertainty, so proper caution motivated the response.

Joshua: I agree: there was significant uncertainty in March 2020 but there were many reasons to be deeply concerned. For my part, I began to examine early transmission data in January 2020 with colleagues and was already involved in a scientific study conducted by an international team analyzing early estimates of the transmissibility of Covid. Our report was released publicly on February 2. The data suggested that without interventions each infected individual was likely to infect ~3 new individuals on average. Moreover, detailed follow-up of initial cohorts in Wuhan suggested that approximately 1 in 100 infections would be fatal (we should return to the issue of infection vs. case fatality rates later). Related work by our team released the following month explored how asymptomatic infections could make the outcome even worse. The math here becomes grim and is precisely why epidemiologists began to issue warnings – rightfully so.

A disease that infects 3 new individuals on average will, in theory, continue to grow exponentially until upwards of 80% of a population becomes infected. There are limits and caveats to any model of epidemic dynamics, but considering this scenario was and is essential. In the United States, if 80% of the population were infected and 1 in 100 infections were fatal, then Covid had the potential to cause more than 2M fatalities. In fact, more than 1.2M Americans died and vaccines are estimated to have saved more than 1 million lives. In other words, as bad as things were, they could have been far worse.

Would one learn the significance of this information as vital context from reading Macedo and Lee? Again, no. I don’t know what the authors know but I can read what they say. They don’t have particular expertise in epidemic or virus dynamics. That gap in expertise comes with a risk. Any interpretation of political decisions that is not equally clear-eyed about the public health risks will have significant limitations. The irony of course is that one of the central critiques of this book is that others (never the authors) were engaged in group-think.

But, of course interventions could have been better. There was confusion of many kinds and one of the biggest mistakes of public health authorities, including the CDC and WHO, is that they tended to communicate in a way that required incontrovertible evidence to ‘disprove’ assumptions that were themselves flawed.

For example, waiting on quantitative evidence of transmission in droplets below a particular size led to confusion and significant delays in communicating facts to the public. This was an avoidable error – one that I explore in detail in my book. And this is precisely the sort of issue that does warrant investigation, e.g., how does the culture of science and the scientific method adapt and adjust in the midst of a rapid-moving threat that ends up moving faster than the capacity of conventional responses and institutional readiness to adjust prior assumptions? But that is not what “In Covid’s Wake” does.

Neither do Macedo and Lee confront how Republican governors and President Trump shared misinformation and advocated for junk cures while claiming that Covid was not as severe as claimed. Perhaps – just maybe – that had an impact. It would seem yet another missed opportunity to not take misinformation from the right seriously.

Greg: By the late summer of 2020, as you and I were advocating for a surveillance program linked to quarantine for Georgia Tech students and staff, we had more data. Sure, young people were quite unlikely to be hospitalized with Covid-19, but two features of SARS-Cov-2 that make it unlike flu had emerged. One is that asymptomatic transmission was rampant: much of the spread was due to people who were unaware that they had the virus. You have written cogently in your book, Asymptomatic, about how this upended standard assessments. The second is that multiple infections within a few months of one another were possible, that immunological protection against a second or third bout was not guaranteed. The transmission ratio was still high, new more virulent strains were emerging, and the only way to stop the spread was NPI and social distancing.

Joshua: I remain deeply grateful that we were able to work together to confront the threat of Covid in our community along with scientists, staff, and students and with the support of the Georgia Tech upper administration. The work was community-based – focused largely on the immediate Georgia Tech campus – while similar efforts were taking place nationally at UIUC, UCSD, Harvard, and beyond. Our effort to develop a scalable intervention contains broader lessons and represented an opportunity to translate principles into action.

As you mentioned, the premise of using testing to slow spread was that asymptomatic infections were common, Covid presented a differential threat with age, and people interact across age groups. This means that many young people might be infected, and more infection inevitably leads to greater risk of a hospitalization or worse – especially in older staff, faculty, and community members. This became the basis for the surveillance program and the communication campaign. We tried our best to communicate the individual risks realistically while emphasizing the importance of empathy and the impacts of reducing infection within the community and when traveling back from campus to visit family. But, if we were to do so, we simply could not wait until people exhibited symptoms.

Instead, a collaborative team and ethos developed. PCR-based testing would be used not as surveillance but as an intervention. Testing at scale would allow us to short-circuit chains of transmission. Of course, this level of testing required investment and buy-in, especially in the absence of mandates, which were themselves prohibited at the state level.

But we did get buy-in and we did make a difference.

In the end, more than 50% of the positive Covid cases identified and reported on campus were via the asymptomatic testing program. These interventions in Fall 2020 and Spring 2021 reduced onward transmission and kept positivity rates below comparable campuses, e.g., University of Georgia, that had a surveillance rather than intervention program.

The entire program is a counterbalance to the idea that non-pharmaceutical interventions can’t work as a gateway to vaccines. And yes, Covid evolved, and we did not get as long an immunological protection window as we hoped – but as is apparent now, buying time matters. Buying time means that more people experienced Covid for the first time post-vaccination rather than when immunologically naive. This is precisely the point. Even if individuals experienced a breakthrough infection in 2021 or beyond, their outcomes are dramatically better than for individuals who declined to be vaccinated. Despite ongoing revisions, the mRNA vaccines were found to be safe and effective at preventing symptomatic illness – reducing the risk of illness by ~95%.

But our work at Georgia Tech also comes with a caution – testing was not available broadly and even with the acceleration and dissemination of rapid, low-cost antigen tests, any decision on how to use and deploy such tests also requires thinking hard about tradeoffs.

Greg: Thanks for that summary of the work we did together, which I too greatly appreciate – as did most of the community. I would add that the obstacles to implementation were initially legal not scientific, but limited resources (things like robots and pipet tips) prevented adoption by other large communities and companies – and for the same reasons most of us remain at high risk in the event of a new pandemic. In any case, the argument that NPIs did not work has always seemed to me a spurious one. People cite a Cochran review of mask wearing that certainly shows that masks alone are not sufficient to get the transmission ratio down to below 1, which is what is needed to stop the epidemic. The point though was always that the combination of factors, masks, social distancing, and ultimately testing, all worked together to reduce the spread and protect more vulnerable people. At some point it became clear that the virus was small enough to get through the pores in regular masks and that the six-foot radius concept was silly. Yet maintaining NPI was still making a difference. I do think that the messaging could have been better, that masks were not about preventing your own infection but rather about protecting others by reducing the odds that you became a spreader. Somehow the individual freedom narrative was allowed to drown out the shared sacrifice one.

Joshua: I agree with the central premise here: interventions are designed to work in combination. But I also want to emphasize a related point: the effectiveness of a technology is not the same as the effectiveness of an intervention campaign. Masks can be effective even when mask policies are not. Vaccines can save lives but only if people get vaccinated.

With respect to the mask debate, in the end, the efficacy of any masking campaign depends on (i) how effective are masks at reducing release and inhalation of infectious viruses; (ii) the relative level of adherence in the population, i.e., whether people use masks in contexts where exposure might happen. Macedo and Lee neglect to separate out these two features. High-quality masks work, but that doesn’t mean that we had enough masks, knew enough to recommend which mask to use, communicated clearly where/when to use masks (i.e., indoors in poorly ventilated settings and not necessarily outdoors), and built an environment where mask use was viewed as a positive, social good. There were massive differences in mask use by state and by region – this too became politicized and I am not sure why the fault of such politicization lies on a single side.

Now, the other fact that is important to sort out is that coronaviruses are small. They have diameters on the order of 100 nanometers or 1/10th of a micron or 1/1000th the width of a human hair. So a single virus may be smaller than a pore of a N95 mask (which is on the order of 0.3 microns), but nonetheless N95 masks can still filter the vast majority of viruses at that size and even more efficiently when viruses are released in respiratory droplets. These droplets come in a variety of sizes – and so from a mechanistic standpoint there is ample evidence that N95 masks work (e.g., one study found that although cloth, surgical and KN95 masks reduced viral emissions, the N95 mask had by far the best features).

Finally, I agree that the issue of the 6 foot rule was indeed problematic. It gave the impression that there was a strict transmission cutoff and that one could physically space individuals in a room and ensure safety. But, in early 2020 there was already a vocal group of public health experts working on Covid who knew that puffs of warm breath could linger in the air and travel far longer than 6 feet. I cover all of this in Asymptomatic – including early evidence of long-distance transmission that were released publicly in early 2020. These are the elements of evidence and missed opportunities that deserve attention.

There was a failure to communicate the most effective ways to reduce infection, despite efforts by many to communicate what the evidence showed: that despite early confusion, individuals could infect others via airborne transmission even in the absence of symptoms. Knowing this opens the doors to individual action taking that also benefits the public good: it means that there are individual benefits to meet outdoors vs. indoors, improve ventilation, wear a mask when in poorly ventilated indoor environments, reduce gathering sizes, and get tested – even in the absence of symptoms. These are all examples where there was a chance for greater alignment between individual choice and public benefit.

Finally, if we had followed the advice of the signatories of the Great Barrington Declaration in late 2020 (an open letter calling for ‘focused protection’ to replace lockdowns, a key signatory is Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, now NIH Director), the US could have seen an even larger surge of infections in an immunologically naive population leading to widescale fatalities – instead, we bought time and spared exposure for many tens of millions who got vaccinated.

Greg: The narrative around vaccines has also got away from us. It is just mind-boggling to me that we could possibly be in a place now where an extraordinary new technology, deployed at unprecedented speed, that allowed societies all over the world to open back up, is now demonized to the point that legislative efforts are being made to criminalize it in multiple States of the US. I am speaking of mRNA vaccines of course, but regular peptide antigens played key roles as well. The risk-benefit ratio for these is tiny, though ironically as someone who has never been diagnosed with nor experienced Covid-19, I have to say my near-death experience came the day after taking a booster when I fainted from high fever and missed cracking my head on a steel-rimmed coffee table by an inch! Perhaps the problem is that people were sold on the idea that the vaccines would prevent infection (technically, they would be sterilizing vaccines), whereas they ‘merely’ give people enough protection to prevent severe symptoms and minimize mortality. You only need to look at countries like Australia and China where lockdowns persisted until over 80% of the country was vaccinated: infection rates were sky high after opening up, but the death rate was low and hospitals were not overwhelmed. Vaccines worked brilliantly.

Joshua: Vaccines worked, as you say, brilliantly (but I will return to the more complex case of China in a moment).

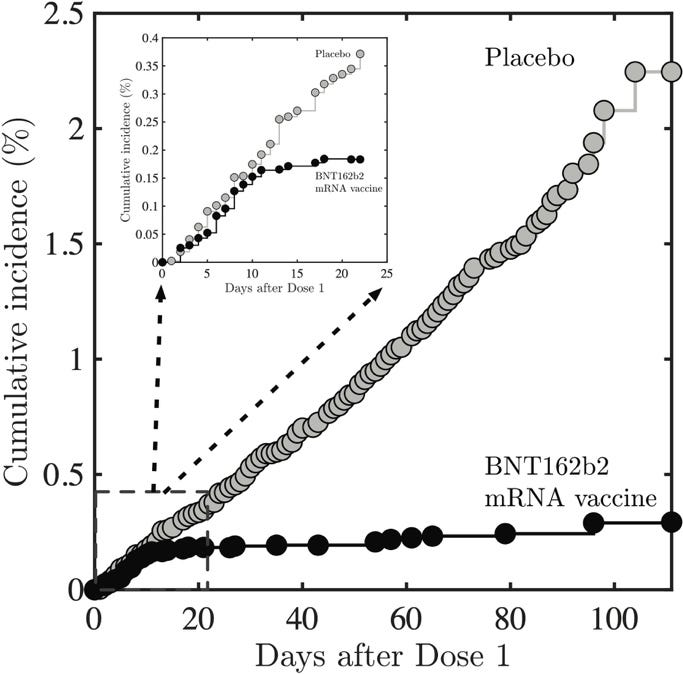

I have written extensively on this on Science Matters, especially in light of the ongoing measles outbreak. For Covid, the effectiveness of vaccines and the importance of vaccination warrants a full chapter in Asymptomatic. So again, let’s get some facts straight. Covid vaccines – including mRNA vaccines - were evaluated based on their ability to reduce symptomatic disease. The image below makes the point clear, it’s adapted from data found in the landmark late 2020 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Compared to placebo in a randomized study with more than 30K participants, the two-dose series of Pfizer vaccines (in this case) was shown to be 95% effective at reducing symptomatic infections. The development and mass production of vaccines took place in less than a year of identification of the virus and the identification of a target – SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein. It’s a modern miracle, the production was enabled by Operation Warp Speed (a serious success of the Trump I administration), and yet all of this is now under threat.

Of course, the effectiveness of vaccines also depends on how many people get vaccinated and how quickly. This is where the US missed an opportunity – with deadly consequences. Vaccines are estimated to have saved more than 1M lives in the US alone. But politicization and misinformation led, as per consensus estimates, to more than 200,000 preventable deaths – because people declined the opportunity to get vaccinated even as many in the world never had the chance to make that choice. These are two interconnected points that Macedo and Lee miss. First, NPIs can reduce infection and buy time. Second, misinformation has real-world impacts. Blaming the ‘left’ for all public health woes is a political choice but it is not one grounded in evidence.

To close this section, I will caution that using China as an example requires caveats.

There is reasonable evidence to suggest that the reopening in China – after the use of less-effective vaccines and under-coverage within older populations – led to a massive surge and upwards of a million fatalities in a few months. One might say this proves the point – the rapid deployment use of vaccines after NPIs can save lives, but choices matter – Australia and New Zealand made better ones. The US is now facing a choice with significant ramifications. HHS, under Sec. RFK JR and supported by the NIH Director are moving ahead with a decision to halt NIH funding for mRNA vaccine technology. The decision is outrageous and will come with near- and long-term consequences to American’s health, economy and our national security. Moreover, in the past few days, Sec. RFK Jr has taken unprecedented steps to remove CDC leadership as part of a deliberate effort to make it harder to access vaccines. If successful, the consequences will be devastating.

Greg: I am intrigued to know in retrospect how you think we should have responded? We did actually have a lot of approaches, amounting to something of a natural experiment in pandemic response. From Sweden to New Zealand, Massachusetts to Alabama, different types of lock-down were enacted. I was critical of the longevity of the Australian response and how severe they were in preventing travel and tracing movements, but they ensured that people and small business were financially supported throughout. In the US, I’ve looked at the numbers and see no pattern whereby the States, like Georgia, that opened-up early did any better economically. They certainly had a much higher death rate in 2021, but voters did not seem to mind. In the end I don’t think there was a correct or best response, we all just muddled through as best we could. The long-term aftermath of high inflation during the recovery, and social division, is going to be with us for the foreseeable future.

Joshua: I have a short answer and a long answer. The short answer is that we could have invested in the technology, public health infrastructure, and socioeconomic policies to align individual and population-level outcomes. As but one example, rather than viewing masks and tests as a scare resource, invest in both and explain when/why they should be used – and then make it easier for people to use them to keep themselves and their community safe. My book elaborates on this central point, albeit through the lens of asymptomatic infections that made Covid exceptionally difficult to confront. Diseases that have a mix of asymptomatic transmission and (occasional) severe infections can lead to catastrophic population outcomes. As such, we need to invest now in developing the public health infrastructure to prevent and respond to emerging pathogens. Are we doing that? Of course not. Instead, stepping away from mRNA vaccine technology, reducing the public health workforce, and dismantling entire NIH institutes and firing CDC leaders will have lasting, damaging consequences. The long answer is one that is still being written.

Greg: Final thoughts? I just don’t think we should be ceding ground to the right on this. The public health response was in some ways flawed, we can admit mistakes prime among which was failing to balance the mental and socioeconomic costs of the pandemic. At the end of the day, though, a million lives (or more) were saved by NPI and vaccines in the US alone, which to my mind should be trumpeted as a great success of public health swimming against ideological currents.

Joshua: To echo this point, it is worth noting that In Covid’s Wake is not the only revisionist book on the market. This July, Simon & Schuster distributed a new book edited by Lawrence Krauss entitled “The War on Science”. Despite what one might think, the book views the ‘war’ as being entirely a product of actions taken by the ‘left’. In a blog describing the book, one of the contributors (Jerry Coyne, a well-known evolutionary biologist, and someone who I used to admire deeply) noted that all 30+ essays focused on the threats to science from the left. How is this possible? Did none of these contributors stop to consider that – even prior to the election of Pres. Donald Trump for a second term – there has been a sustained, effort to undermine science from the right? Has no one read Merchants of Doubt, really?

I worry about the presence of similar ideological blinders within “In Covid’s Wake”. I am grateful that it has prompted us to have this particular dialogue, but in doing so, there is a presumption that we should take the book’s arguments in good faith. That is part and parcel of what we are supposed to do as academics – but doing so has a vulnerability, it makes fields vulnerable to those who would exploit a system built on trust and good-faith arguments to the promotion of partisan ideology that fits data to narrative and not the other way around. If we had finished this dialogue a few months ago I think any final thoughts might have been provisional given the rapid and chaotic changes in the new administration. But now the administration’s plans are clear and the books – whether “In Covid’s Wake” or “The War on Science” – appear ever more clearly as advancing bad-faith arguments and contributing to the acceleration of attacks on science that undermine experts, expertise, and public health. The books ask readers to bury their heads in the sand, as it were, and not view past and present threats for what they are.

Greg: As I think you know, I am working on a book, “Virtue Genetics”, which has required some brushing up on my Aristotle. One of the core concepts of his ethics is practical wisdom, the notion that it is insufficient to just think about or understand a situation, you need to work out how to act with the appropriate moral motivation to produce change. Camus seems to embrace this as well when he writes “The evil in the world comes mostly from ignorance, and goodwill can cause as much damage as ill-will if it is not enlightened. People are more often good than bad, … but they are more or less ignorant and this is what one calls vice or virtue, the most appalling vice being the ignorance that thinks it knows everything and which consequently authorizes itself to kill.” Practically speaking, I think public health experts underestimated how to communicate their intent against a background of economic and mental health hardship during the pandemic. Hopefully we have learned from that. But remaining ignorant of the consequential effectiveness of NPI and vaccines seems to me a vice with potentially devastating consequences. It is demoralizing for health workers doing the right thing for the right reasons, being shot at in their CDC offices and being accused of over-reach, instead of being given full-throated support for their virtue.

Joshua: I could not agree more. The stakes are high and the consequences of decisions made in the months to come will reverberate. Just a few days ago, William Foege – the physician who designed the strategy to eliminate smallpox – wrote an OpEd in Stat News. Perhaps he should get the last word: "[T]hose working in public health must continue to keep the objectives of their profession in mind: prevent premature death, reduce unnecessary suffering, and improve the quality of life for everyone... Do not back down."

Thanks guys, I appreciate this thoughtful dialogue so much. For so many like yourselves who worked on Covid daily from the beginning, this bizarro world rewriting of history is so maddening… and ultimately dangerous, as you suggest.

This is the best and most informative corrective to the Macedo and Lee book that I have seen. Thank you for conducting this very interesting interview.